The Great Divide

Emperor Theodosius’ death in 395 solidified the linguistic and cultural separation between the Latin West and the Greek East within the Roman Empire. The subsequent decline of the Western Empire led to dwindling contact between the two regions. As a result, knowledge of Greek gradually faded in the West, just as Latin receded in the East.

Rediscovering Greek in the Latin West

While it is true that Greek was not widely known in the Latin West between the 5th and 15th centuries, our research uncovers intriguing glimpses of Greek knowledge among a select few learned individuals. Furthermore, many more individuals in this period were aware of the significance of Greek. A notable example is Theodore of Tarsus (602–690), a Greek speaker who traveled to England and assumed the role of Archbishop of Canterbury in the 7th century.

The Extent of Greek Knowledge

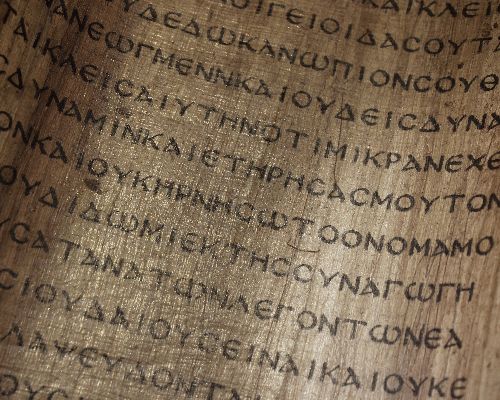

When discussing knowledge of Greek during the Middle Ages, we primarily rely on written evidence, which provides us with limited insight into conversational fluency. Sources suggest that interest in Greek among Latin-speaking medieval Europeans was primarily confined to religious and scholarly contexts, with little emphasis on its practical use as a means of communication.

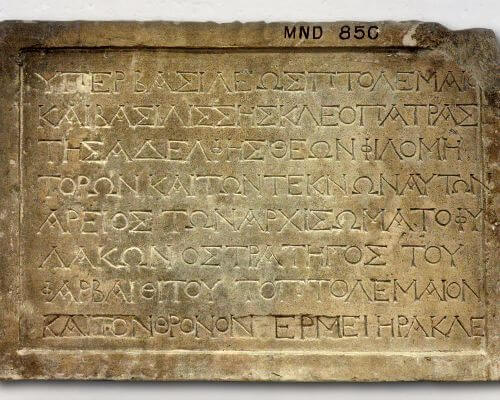

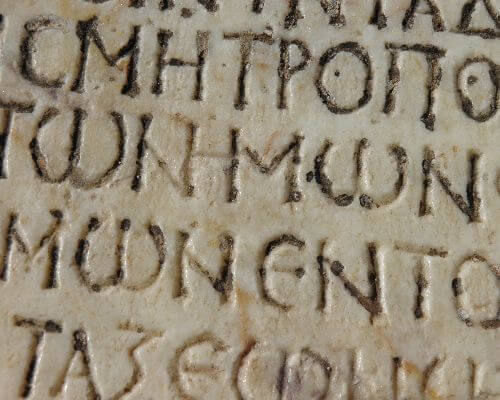

Traces of Greek in Western Manuscripts

Evidence of Greek influence in the Latin West can be found in numerous manuscripts. It was widely known that the New Testament had originally been written in Greek, and references to Greek scholarship and literature were prevalent in texts popularly copied in the early medieval West. For instance, the works of Cicero often included brief excerpts from Greek, while the poems of the Christian Latin author Prudentius, widely read during the Middle Ages, frequently bore Greek titles. Although these titles were sometimes written in Greek letters, they were more commonly transliterated into Latin. An exceptional example of Latin transliteration can be found in the 9th-century Athelstan Psalter, where the Greek litany and prayers are rendered in Latin letters.

Educational Endeavors: Bridging the Language Gap

During the Carolingian era, a plethora of glossaries, dictionaries, and grammar handbooks emerged, serving as resources for Latin speakers in the West seeking to learn Greek. This is particularly evident in word-lists, which were often simply reversed from Latin–Greek to Greek–Latin. Additionally, aids in understanding Greek included idiomata—lists of words in which grammatical rules differed between Greek and Latin. For example, a list of Latin nouns might be accompanied by their corresponding Greek terms, even though they belonged to a different gender. One of the best-known sources for the study of Greek in the medieval West is the Hermeneumata.

This collection, with its alphabetized glossaries, topical word lists, simple texts for reading comprehension (such as fables), and colloquies describing everyday life, sheds light on the educational practices of late antiquity.

Despite the absence of widespread Greek knowledge among intellectuals in the Latin-speaking West before the Renaissance, many surviving manuscripts demonstrate the efforts made by Western scholars to learn Greek.